Konrad Vechta's Bible or Wenceslas Bible is one of the finest illuminated manuscripts in the collection of Museum Plantin-Moretus. Vechta ordered his bible around 1402 and it was expensive: the book is luxuriously executed and lavishly decorated. You will find 210 miniatures and even more illustrations in the margins. Among other things, Vechta was archbishop of Prague and mint master of the Holy Roman Emperor and Bohemian king Wenceslas IV. High society, in other words. But appearances can be deceiving, because the Bible he ordered was never finished. Probably because of financial problems. Nevertheless, the Vechta Bible is an example of the heyday of Bohemian illumination of the late 14de century.

Drôleries

The manuscript is illuminated. This means that the handwritten pages are decorated, something often seen in medieval manuscripts from the 13th to 15th centuries. Drôleries are a subcategory within illumination. They often look funny. Think, for example, of medieval rabbits riding snails, or burned drawings of nuns picking penises from trees. Often illustrate puns or jokes with which medieval readers were familiar but we are no longer. They referred to the main text, commented on it or interpreted the message in a funny way.

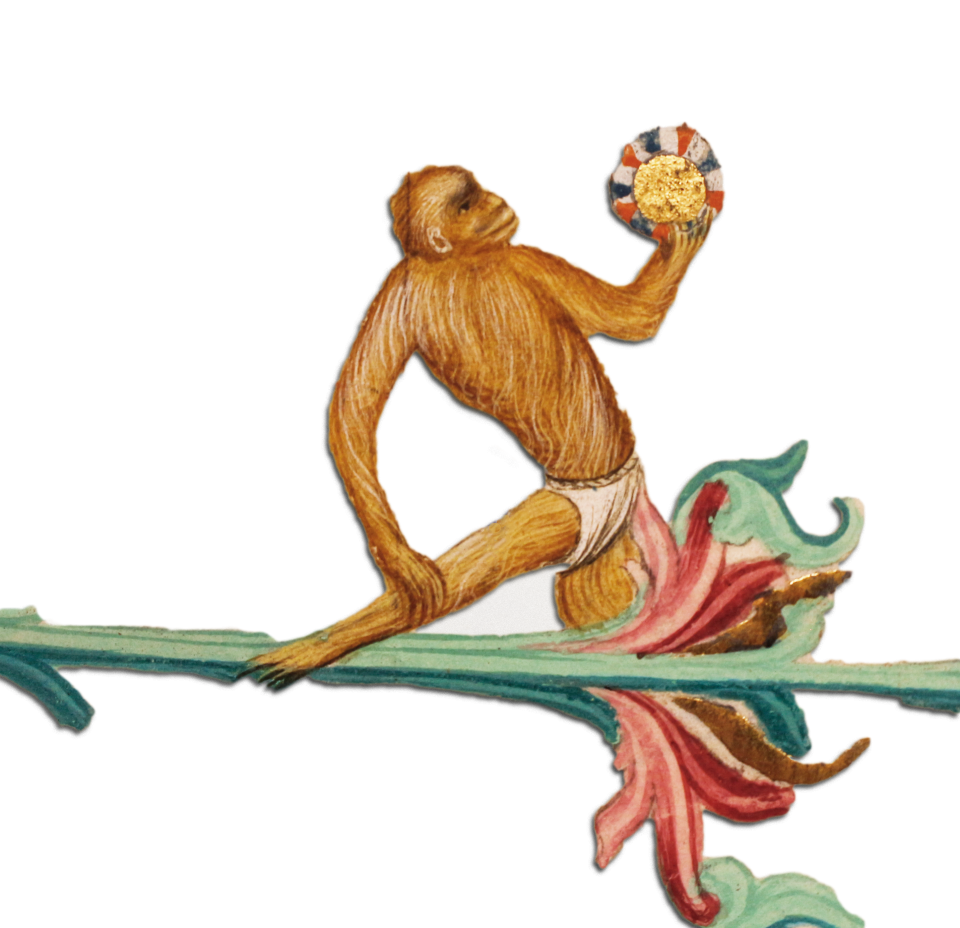

Something is going on with the characters in Vechta's Bible. In fact, beneath those comically bouncing around bears and monkeys is a deeper layer of meaning. They tell a religious story and symbolize love for and connection to the king's knightly order. In this blog post, we take a closer look at a particular theme depicted in the margins of Vechta's Bible. This will give you more insight into the symbolism of the fascinating decorations found in the manuscript.

Carnal lusts and earthly temptations

The drôleries in Vechta's Bible reminded readers to live piously and be loyal to the king. But how was that meaning conveyed by depicting cute, human-like creatures? First, we need to understand how medieval readers interpreted those creatures. The bear, for example. It was once seen as the king of the animal kingdom and was often depicted as a demonic creature. Bears can walk on their hind legs and were often regarded as "the man of the forest." Medievalists thought the bear was closely related to man, along with the monkey and the pig. So that trio was often used to parody humans. The bears in Vechta's Bible play instruments such as the bagpipes or the lute. They refer to the animal passion that can flare up when listening to profane music. The Church considered that kind of passion sinful, a temptation of the devil.

Criticism of shortcomings

Another function of the animals is to "secretly" parody real people who resided at or near the court. For example, Vechta himself is depicted as an ibex, the sign on his coat of arms. He drinks beer from a medieval lager glass.

Even the king himself does not escape the illuminators: he is depicted as a stern-looking rabbit jousting with a ram. The images seem intended to be funny, but actually they illustrate the shortcomings of these important figures. In Vechta's case, the hearty pot of lager is a reminder to drink less.

Cryptic decorations

These drôleries often followed exempla. Anecdotes or stories that were told but had nothing to do with the content of the actual text. That kind of embellishment is very cryptic. You have to know the narrative to interpret an individual performance. It is clear, however, that many of these stories deal with stupidity, love, or both. For example, consider the monkey admiring herself in the mirror. She depicts a phrase popularized by the minnesinger Burkhart von Hohenfels. He told his lover that she enchanted him like the wild ape is enchanted by his own reflection.

Variations on that motif recur on other pages. Sometimes with a bear, other times with a monkey leaning on a stool.

All are examples of how you should not behave and what you should definitely not pursue.

So there is a contradiction between what goes on in the margins and what goes on in the main text of the manuscript. Often that contradiction is further reinforced by downright evil symbols, such as owls and flies.

On love and other matters

The lure of the flesh is not the only theme in the border decoration. The illuminators also illustrated a purer ideal: that of courtly love. The depiction of the virgin and the unicorn, for example. These can be interpreted in different ways. The most common allegory is that of a young courtier riding a wild unicorn.

The fabled beast can only be tamed by love in the womb of a virgin. Usually that allegory is a religious reference to the announcement of the birth of Jesus.

Another symbol of love are the two "lovebirds" in the margin: a brown-black bird with a red crest and a green parakeet. They sit near each other all the time and peer at each other.

Bladeren en stengels van de Acanthus.

There are also more imaginative and decorative figures. In Vechta's bible, the leaves and stems of the Acanthus (a Mediterranean plant) appear often. Among all the foliage, birds, dragons and other fantastic creatures look at you, or nibble at the vegetation. This is possibly a metaphor for the reader who, like the animals, eat the words in the book.

Vechta's Bible is full of drôleries that interact with each other and convey different messages to the reader. It is difficult for our modern minds to fathom those messages. Sometimes we simply have to accept that the medievalist liked to laugh at depictions of himself as a beer-drinking bear.