Exploring Ortelius' legacy

Abraham Ortelius is a significant figure for the Museum Plantin-Moretus, as he was a close friend of the printing family and worked closely with the Officina Plantiniana from 1579 onwards to publish his atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Christophe Plantin had already been involved in the publication of the first edition in 1570, when he supplied the paper for this groundbreaking work. Ortelius’ atlases are a crucial part of his legacy, which is why the museum has previously hosted exhibitions on this topic, in 1998 and again in 2014 and 2015. In the run-up to 2027, the museum will also initiate a collaborative project with other cultural institutions to highlight Ortelius’ many achievements.

This collaborative initiative will include thematic collection presentations hosted by the participating institutions. The Museum Plantin-Moretus will serve as a central hub for the celebrations. As a key partner in the network, the museum will host an on-site exhibition. A series of public programs will bring Ortelius' work to life in diverse and engaging ways. These will include a symposium, public lectures, and workshops. These events will offer opportunities for scholars, as well as the general public to engage with Ortelius' legacy in a variety of ways.

A dedicated website will serve as a virtual gateway to the anniversary celebrations, offering detailed information on Ortelius’ life and work, as well as updates on events and exhibitions.

Through these collaborative efforts, the project will not only celebrate Ortelius’ achievements but also foster a deeper understanding of the historical and cultural impact of his work. This network of cultural institutions, with the Museum Plantin-Moretus at the forefront, is poised to create a year-long celebration that will engage audiences from around the world in a deeper exploration of Ortelius’ enduring legacy.

Partners

- Museum Plantin-Moretus

- James Ford Bell Library, University of Minnesota

- The Newberry Library

- Minneapolis Institute of Art

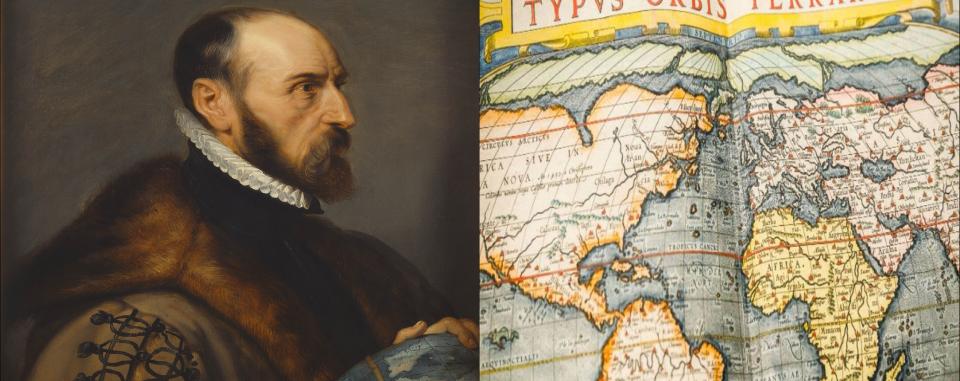

Who was Abraham Ortelius?

Abraham Ortelius (also known as Abraham Ortels or Hortels) was born in Antwerp on April 4, 1527. He grew up in a family of three children, with two sisters, Anna and Elisabeth. From the age of ten, he was raised by his uncle, Jakob van Meteren. Throughout his life, Ortelius lived in Antwerp, close to St. Andrew’s Church, alongside his sister Anna. He never married.

Ortelius is best known as a cartographer, mapmaker, and kaartenafzetter (colorer of maps and illustrations, a profession he began in 1547). He is often regarded by the general public as the ‘inventor’ of the modern atlas. Beyond his work in cartography, Ortelius was also a passionate collector, amassing a wide range of art, maps, paintings, portraits, stones, natural curiosities, antiquities, prints, books, coins, and medals. His expertise and contributions to the field earned him the title of royal cartographer to King Philip II of Spain.

In addition to his work as a mapmaker, Ortelius was involved in the print and book trade and was active as a publisher of maps. His most famous work, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, was first published in 1570, printed by Gillis Coppens van Diest, and featured 53 engraved maps. This atlas became a significant milestone in the history of cartography.

Ortelius maintained an extensive international network, which is documented through his surviving correspondence. At least 376 letters are cited in the work of Hessels, with 337 traceable to institutions. Of these, the location of 39 letters remains unknown. Additionally, there are at least 169 letters not mentioned by Hessels. Ortelius traveled regularly across Europe, further expanding his professional connections and influence.

Ortelius, the mapmaker

In 1547, Ortelius is registered as a kaartenafzetter (map seller) in the lists of the St. Luke Guild, where he colored maps and prints for individual clients and printer-publishers, including Christophe Plantin. By 1550, he inherits the family business as a dealer in prints. Then, Ortelius begins designing wall maps of regions such as Egypt, Asia, Spain, and the Roman Empire. In 1570, he published the first Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, a groundbreaking atlas that gathered maps created by various cartographers, presenting them in a uniform format, style, and structure. Ortelius also added a list of sources that he relied upon, shedding light on the intellectual foundations of his work.

Ortelius' maps, like those of many early modern cartographers, are more than just tools of navigation, they are snapshots in time. During this period, travelers and navigators were continually expanding their understanding of the world through firsthand observation. This growing body of knowledge was then processed by cartographers, astronomers, and geographers, who would transform the information into maps. These maps inspired debates, new theories, and treatises that in turn influenced travelers and navigators, who used them to refine or correct their own knowledge. In this sense, as soon as maps came off the presses, they were already outdated, demonstrating that a map is never truly finished. Furthermore, a map is not just a reflection of geographical data—it is deeply influenced by its maker, the culture it represents, the moment in history, as well as ideologies, religion, and even emotions. A map is shaped by the worldview of both its creator and its user.

Maps are an invitation to verify the information they contain against reality. They offer a balance between too much and too little information, with blank spaces often filled with titles, illustrations, and texts. What is omitted from a map can be as significant as what is included. A world can be depicted not only in a map, but also through words (as seen in the text parts of Ortelius’ atlases), colors, shapes, and even music. The question of how much fantasy is embedded in the depiction of the world is central to understanding early modern atlases. Maps are an amalgamation of facts and guesswork, drawn from accurately measured coordinates with scientific instruments, but also reflecting the imagination of a changing world. They are simplifications, abstractions, and distorted images—hypotheses rendered in symbolic language. A map programs its viewer's perspective; it shapes what one sees and draws attention to the features it emphasizes. By choosing what to depict and what to omit, a map does not just represent reality—it actively intervenes in the way that reality is understood and experienced.

Ortelius, the collector of art and knowledge

Ortelius was also an avid collector, and his extensive network of humanists and artists allowed him to expand his collection. He acted as a middleman, acquiring miniatures, oil paintings, and illustrated books for other collectors, effectively bridging the worlds of art and scholarship to facilitate the exchange of both art and knowledge. He traveled frequently to research the remnants of the ancient Roman provinces, carefully observing and documenting his findings.

As a print dealer and associate of Christophe Plantin, Ortelius understood the power of printing to unite these two worlds. Printing offices were ideal spaces where artists and humanists came together, creating networks of scholarly and artistic knowledge. Ortelius' library served a similar role, acting as a meeting place for both scholars and art enthusiasts.

We can think of Ortelius’ house as a cabinet of curiosities. In addition to a library filled with books and manuscripts, he collected various objects, including paintings, sculptures, Greek and Roman coins, shells, marble, turtle shells, and more. Cabinets of curiosities were designed to bring together objects and art, with the aim of expanding one’s understanding of distant and ancient cultures.

Ortelius, the networker

Ortelius' extensive network is still traceable today through his surviving correspondence. After his death, his nephew, Jacobus Colius, inherited more than 300 letters, including those sent to scholars and artists such as Emmanuel van Meteren, Justus Lipsius, Pieter Breughel de Oude, Maarten de Bos, Alexander Farnese, Benedictus Arias Montanus, and many others. These letters offer valuable insight into Ortelius' intellectual circle and the relationships he maintained with prominent figures in scholarship, art, and science.